Putting visuals into science journalism

Watch the following 16-minute video that features interviews with Dr. Joan Leach, senior lecturer in rhetoric and science communication at The University of Queensland (UQ), and Dr Peter Milne from the School of Journalism and Communication at UQ.

Dr John Harrison, senior lecturer in Communication and Public Relations at UQ, interviews Drs Leach and Milne about why the visual is central to good science journalism.

How to think visually

The following tips are to get your mind into the space of considering how visuals can add to your reporting on science issues. Below these tips, we present the topics of:

- What do you want to say, and who to?

- Designing visuals and infographics

- Logistics and technicalities

- The beautiful intersection of art and science

1. Think visually. Train yourself to think about the visual. Make special note of good visualisations that you see in newspapers, magazines and online. Bookmark sites that have good visuals, such as the New York Times.

2. Ask your sources. When sourcing a story ask your sources for images, or for about how their story might be represented visually.

3. Become familiar with visualisation tools. The more you use them the better you will become. If you want to create an infographic—a graphic, visual representation of information, data or knowledge—here are some links to free, simple-to-use tools that we have recommend:

- Infogram is a free online tool to create interactive infographics.

- Piktochart helps you create infographics, share them and get results.

- easelly, while still in beta, is an online app that lets you create infographics and visualise data using themes.

4. Source images from Flickr. Flickr is an image sharing site and you can access and use images under a Creative Commons license from Flickr. There are no fees attached to Creative Commons licences. Make sure you read the Creative Commons conditions of use.

5. Infographics versus text. Are infographics better than text plus pictures? Always ask yourself can the story be told better as an infographic rather than as just text, or text plus pictures.

6. Information with feeling. In the video, Peter Milne says you should always ask the question: what do you want your audience to feel? Do your visuals convey the ‘feeling’ as well as ‘information’? You might also want to have a look at the Telling a science story to engage the audience module for ideas on this.

7. A responsibility beyond text. If you don’t draw an audience in to your report, whether that’s through an image or an interesting headline, your perfectly crafted words will never be read. So, in terms of both the audience engagement and the integrity of the story, remember that that the text is not the only responsibility you have. Your communication is always enhanced by the visual.

Exercise

Find an example of an infographic that is trying to explain science. Please include a link to the infographic in your answers or paste a copy.

How is the infographic used? As part of a story or as a stand-alone diagram? How well do you think it explains something scientific and complex compared to just using words? How could it be improved? Does it evoke any emotions in the reader/viewer of the infographic? If so, how does it do this?

Designing visuals and infographics

Icons and illustrations can help you summarise complex or emotionally charged information. At a glance, people should be able to take away something without reading the text.

The mix of images vs text

How you construct, or design, the text and images is also a part of the storytelling experience. Use the graphics, pictures, or models to tell a story. At a glance, people should be able to take away something without reading the text. Lean towards more graphics and white space—make it a pleasure to read, not just easy to read.

Make sure you get a professional editor to edit text in your graphic/image, because it reflects the credibility of your report. Brief the subeditors and editor on the writing style and tone you want. Do you want to sound formal or chummy? Is some jargon ok? It depends on the audience and the purpose of the visual.

Colour

Colour, sparingly used, is a very useful visual cue.

Choose colours that are appropriate to the information, and take colour blindness into consideration. Some infographics use few colours but are still effective.

Colour, if used without thought, can also limit the success of your infographic. If, for example, you use the colour red to communicate danger and, in the same infographic, you use red and blue to distinguish female and male, people may perceive your information about females as negative.

Greenpeace’s Boom goes the reef uses the colour red to communicate danger and negative emotional messages about the impacts of Australia’s coal exports on the Great Barrier Reef.

Numbers

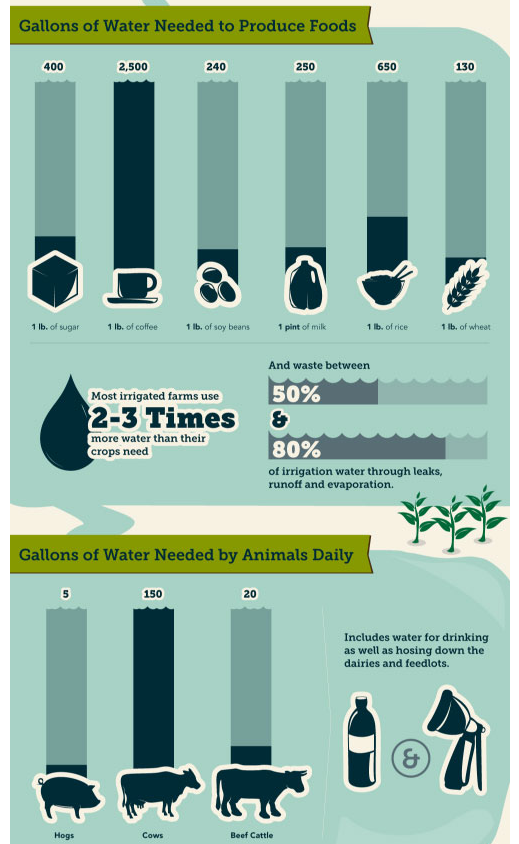

A poorly designed visual can mislead your readers/viewers.

In this Gallons of Water example, your first impression might be that the range of the y-axis scale is 0 to 400 gallons (bar 1, sugar) when in fact it is 0 to 2,500 gallons (bar 2, coffee).

The number of gallons for each product other than coffee should be positioned lower down the bar, aligned relative to 2,500.

Interactivity and moving visuals

These are fantastic examples for their simplicity and ‘clean’ feel:

- Car sharing: Learn about the benefits of car sharing and find car-sharing businesses in your country. It is simple, clean and linear. You can move the car using your keyboard and click on pop-up links that interest you.

- Is the internet awake? How many people in each country are on the internet and at what time? When is the best time to tweet for maximum attention?

- Collapsing bee colonies: How many years would we survive without bees? This animated video infographic explains why bees are important for our survival, why they are dying and the research that has produced a solution. It doesn’t try to overload you with too much data.

- The Climatedogs Enso, Indy, Ridgy and Sam—a pack of cute-looking animated sheepdogs from Victoria. They were developed to help farmers understand the 4 main climate processes that affect rainfall variability in Victoria. 60–90 seconds is all it takes to explain these complex concepts.

Structure and layout

A good page layout channels interest throughout your story. Not only is it worth considering your words and visuals, you may also like to sit with your production team to talk through a page design that will really tie your story together.

You can use shapes and colour to guide the viewer through; remember, a block of text is also a shape.

Keep white spaces between elements consistent—white space directs the eye to the key images, while allowing the design to ‘breathe’.

And keep visual cues (e.g. highlighted boxes, coloured coding headings or information, arrows) to a minimum—use sequences of elements to get your points across. Visual full stops (e.g. token pictures) distract the viewer from the message.

If you’re struggling with layout, print it out, then turn it upside down. If it still looks balanced, it is!

You can structure the information and draw relationships by using visual tools such as:

- numbers

- timelines

- size comparisons

- simple scales

- colour

Logistics and technicalities

Some of these considerations obviously depend heavily on what format your visual ends up in—newspaper, web-only, magazine, TV segment…

We recommend that you:

- Design principles for TV, display, newspaper, the web can be quite different—do some homework! Go and look at other visuals and see what works for you.

- Consider where the visual will end up. What will be displayed/shown near your visual? Where will people see it? How long will people have to view it?

- Get a concept design as early as possible. Use dummy text and focus on the overall look and feel. You’ll avoid expensive design changes at the layout stage.

- Do a few quick drawings of your ideas before you start in earnest.

- Show other people your design, and ask their opinions. Don’t take it personally, they’ll often see things you don’t after working on it so closely.

- Test the design and content with a sample audience. This is to make sure messages are clear and the target audience finds it readable before final production.

- Make sure you and your graphic designer and/or printer are compatible. Technical aspects of graphic production are equally as important as good design.

- Agree on the size. An unusual size will help your piece stand out but may cost more in design, printing and postage; colours (full colour is not always necessary).

- Budget for images. You’ll need high resolution images and you may need to pay for them, although there are many free image libraries on the web.

- Add a title, introduction and alt text (text associated with an image that conveys the same essential information as the image; essential for accessible documents for disabled readers) to your final image so that search engines can find it (they can’t ‘see’ the text in a jpg).

Exercise

Find a science article or news story that currently does not have an infographic, but which would benefit from having one. Draw up a rough outline of an infographic that could be used with or instead of this article/story. Explain why you think this infographic would be useful to the readers.

The beautiful intersection of art and science

These resources may inspire you the next time you want to combine science and the visual world.

- Amorphoscapes by Stanza examines the audio-visual relationships between art and science.

- Art & Science Collaborations, Inc.—an eclectic group of individuals who are interested in the intersection of art and science.

- Arts Catalyst: The Science-Art Agency—working to extend, promote and activate a fundamental shift in the dialogue between art and science and its perception by the public.

- Australian Network for Art and Technology (ANAT) activates creative connections and collaborations, nationally and internationally, amongst a diverse network of people and organisations working at the forefront of the art and culture, science and technology nexus.

- CUNY Graduate Center New Media Lab: Science and the Arts—produces events and projects that bridge the two worlds of art and science.

- Daniel Langlois Foundation for Art, Science and Technology—working to further artistic and scientific knowledge by fostering the meeting of art and science in the field of technologies.

- Gene(sis)—an exhibition of powerful new artwork reflecting recent developments in genomics.

- L’Oreal Art And Science Foundation awards an annual colour prize on the theme of the meeting of science and art in colour.

- Projects for a New Millennium is a non-profit organisation that creates collaborative events that foster the fusing of art and science as a means of discovery and appreciation of the natural world.

- Science and the Artist’s Book—Smithsonian exhibition that explores links between scientific and artistic creativity through book format. Classic volumes in the history of science are the starting point for works by participating book artists.

- Synapse—the Synapse database is an Australian online resource promoting the nexus of art and science.

- Tate in Space—research and development program looking into the feasibility and practicalities of housing future collections in space.

Check out all the exercises for this module.

Scijourno is a collaborative project

|

|

|

The University of Western Australia also contributed to the academic advisory group.